Since the November 2020 COVID-19 vaccine announcement, global bank shares have rebounded sharply on expectations of a robust economic recovery. Investors are increasingly optimistic that banks have turned a corner after years of disappointing performance and are likely compelled by 1) the combination of valuation metrics that are far lower than global market averages and 2) the potential for re-rating if the sector becomes more “utility-like” with its high shareholder yields in a low-rate environment. This prompts the question “Is there more value to be unleashed or do the risks outweigh the rewards?” Banks operate highly-leveraged and often commoditized business models impacted by significant macro and regulatory forces outside of their control. It is dangerous to generalize, but we see significant disruption on the doorsteps, which is not reflected in the near 13-year high absolute valuations.

We asked two of our analysts, Rich McCormick (global financials) and Glenn Cunningham (global technology), to discuss their views on the banking industry. They see underappreciated technological and private capital disruption on the horizon as new players attack banks’ highly profitable small business and consumer segments through a combination of low costs, superior technology, lower required returns, lower regulatory burden, and better user experience. Jamie Dimon, CEO of JP Morgan Chase, summed it up well during the firm’s 4Q 2020 earnings call:

“As the importance of cloud, AI and digital platforms grows, this competition will become even more formidable. As a result, banks are playing an increasingly smaller role in the financial system…I’m confident we’re going to be able to compete, but I think we now are facing a whole generation of newer, tougher, faster competitors…I expect it to be very, very tough, brutal competition in the next 10 years. I expect to win, so help me God.”

Q: How does Altrinsic analyze the banking industry?

Rich McCormick (RM): As a firm we have been studying global banking models for over 30 years. Our approach is always to carefully blend inputs stemming from our deep industry knowledge with an extensive cross-border global perspective. In doing so, we take a private equity approach, assessing these companies as if we were to buy them outright with our own capital, analyzing the key drivers of future profit generation, and forecasting this forward using normalized and conservative assumptions. Banks often screen attractively on common “value factors” (e.g. price-to book, price-to-earnings, etc.) but deserve these valuations given their lower returns on equity (ROE), commoditization, high leverage, and opaque business models. When seeking investment opportunities in banks, we focus on those operating in disciplined competitive environments with relatively low regulatory interference, good underwriting discipline, and strong service cultures. Increasingly, however, we see much of the banking space as being at risk for significant disruption by fintech firms and other players.

Q: Is disruption a new phenomenon?

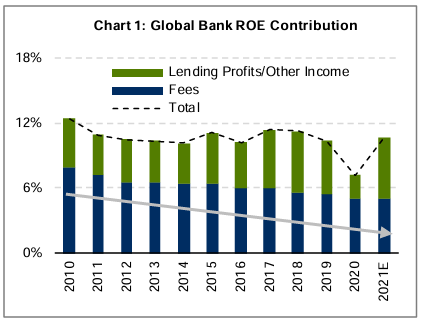

RM: Banks have been battling disruption for decades but the risks are accelerating. As we reflect upon the last ten years, most market participants attribute lower interest rates as the driver of bank ROE compression, but the reality is that disappointing fee income was a much more important factor (Chart 1). This phenomenon took place during a very supportive environment for the banks, including a bull market and secular growth in electronic payments.

Glenn Cunningham (GC): I agree, and competitive intensity is only going to rise. This is a structural change. Banks were the original platform companies, acquiring customers and monetizing them via additional products, a strategy Wells Fargo made famous but that eventually resulted in scandal and failure. Today, there are multiple internet-scale platforms with over one billion users, immense troves of data, and unparalleled execution abilities. Just look at Apple Pay, which now accounts for more than 5% of global transaction volume¹ or Square, which grew its user base for its Cash App from nothing to 38 million in three years. Rapid user acquisition is a core competency for consumer tech companies. As these tech companies’ focus shifts toward monetization, it will further pressure the banking industry’s structurally less efficient business models.

RM: I would also add that the money being put to work in financial technology is significant. Fintechs received nearly $200 billion in funding from private equity and venture capital in the last five years alone², nearly four times the level of the prior five years. Many of these investments are likely to fail, but the flood of capital will ensure a steady flow of innovation.

Q: Why have tech companies zeroed in on banking services as an opportunity?

GC: There are a few reasons. First, the opportunity is massive at $5.5 trillion, based on McKinsey estimates³, making it one of the few markets large enough to meaningfully move the needle for the big tech companies. Second, banks have high operating margins (typically in the 40% range) and are human capital-intensive, which is extremely compelling to tech companies with a cost advantage and lower capital demands (Chart 2). Third, financial services products are critically important to consumers and are used frequently; tech companies want to add these services to increase the stickiness of their platforms and are uniquely positioned to gain share via better products and differentiated user experiences. Finally, tech companies have a significant innovation advantage. Total bank IT spending in the US is estimated to be about $90bn and only growing in the mid-single digits percent per year, with more than 50% going towards supporting legacy applications. By comparison, this is less than the current capital spending by Google, Microsoft, Amazon, and Facebook, which has more than tripled in the last five years.

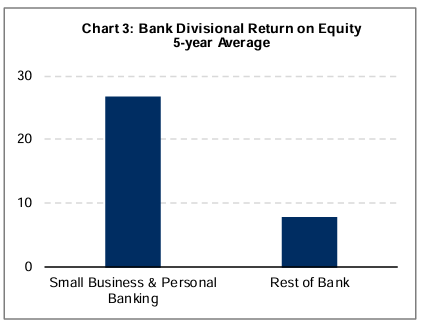

RM: Many tech companies see considerable opportunity in the small business and personal banking space. For decades, banks have subsidized low-return corporate banking with highly profitable small businesses and households. In fact, small business and consumer banking typically accounts for 20% of bank capital, but 50% of profits as ROEs of those areas are three to four times the level of the rest of bank (Chart 3). These more profitable customers are also the most likely to convert to technology platforms given they require simpler services and can transition more easily. The rapid growth – and recently announced plans to go public via a SPAC merger – of fintech startup Acorns is just one example of consumers’ willingness to adopt new tech-driven platforms for their banking and investing needs.

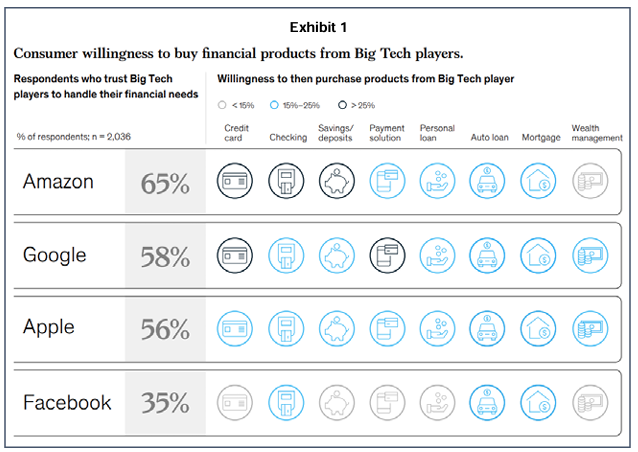

GC: This is a key risk for the banks. Tech companies compete on better user experience, simplicity, and transparency and consumers are increasingly willing to buy financial products from – and trust – non-traditional banking partners (Exhibit 1). The outsized profitability that banks have historically earned in this area was often aided by a lack of transparency, increasingly a faux pas in today’s society.

In addition to the attrition risk – losing small business customers to fintech players – there is also a pipeline risk as fintech platforms enhance their tools and services. Business owners who start out managing their finances and funding through fintech platforms like Square, Stripe, or Quickbooks now find fewer reasons to migrate toward a traditional bank because the sophistication of the offerings by non-traditional players has increased notably to meet demand.

Q: What areas of banking are most at-risk?

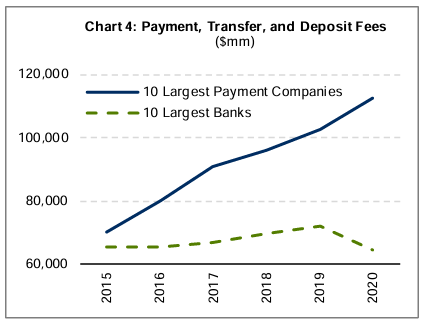

GC: Payments is the obvious area. It accounts for nearly 20% of global bank profits 4 and is structurally growing as cash usage declines around the world. We’ve already seen the impact of new competition here. Despite the dramatic growth in electronic payments over the last five years, banks were unable to grow their payments franchises (Chart 4). Increasingly, tech competitors are winning based on user experience and trust rather than price and are finding ways to build in other products and services that siphon off more banking business.

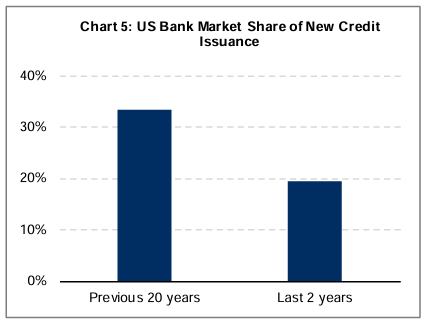

RM: The rise of private credit is an area that we are watching as well. Banks have competed with bond markets for decades but in the current “hunt-for-yield” environment, many investors are interested in other lending vehicles. Increasingly, private credit competitors, like private equity, are utilizing this lower-return threshold along with fewer regulatory hurdles to gain share (Chart 5).

Another consideration is the future possibility of central bank digital currencies; in our opinion, this is a “low probability but extremely high consequence” event for banks. Particularly in Europe, a rise in central bank digital currencies could push banks out of the value chain for certain basic deposit-taking activities that are crucial to much of their business. W

Q: How have these trends played out in emerging markets compared to developed markets?

RM: Emerging markets have actually been on the forefront of many areas of fintech – particularly digital bank adoption – and can help provide insights into the future for developed markets. Brazil’s Nubank, which counts Berkshire Hathaway as an investor, has more than doubled its user base to 35 million people in the last two years alone. Tinkoff Bank in Russia started with credit cards in 2007 and has used its digital platform to build its business into personal loans, small business credit, payments, and investments. After quintupling its loans in the last five years, it is now Russia’s third largest bank, operating at a 40% ROE. WeBank was launched in partnership with Chinese Internet giant Tencent in 2014 and already has 270 million Chinese users through a low-cost digital strategy that utilizes cloud computing and AI. So far the ticket size of new customers is small but new products are growing rapidly.

GC: China is a good example. The country is, in many ways, a model of what could eventually play out around the world. Alibaba and Tencent succeeded in creating “super-apps” that offer all of the services needed for daily life. Fintechs in China now capture 50-70% of all spending in the country. We have many stories of our analysts wandering around Shanghai searching for an establishment that accepts cash!

RM: Chinese banks bore the brunt of fintech competition, with the Big 4 banks shrinking their card profits by 30% over five years despite robust spending patterns. The tide appears to be turning of late with heavier regulations being enacted throughout the fintech landscape. e are monitoring this closely.

Q: Do you expect disruptive forces to impact the developed markets players?

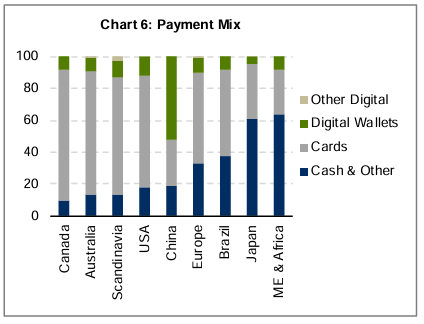

GC: Absolutely. Take Japan, for example, which is still heavily cash-dependent (Chart 6). The government is pushing the economy aggressively towards electronic payments. The companies driving this transition are all tech companies. PayPay, the market leader, is backed by Softbank and uses technology from Paytm in India. They are following the playbook of other emerging countries and attempting to create a “super-app” for Japan. The banks are nowhere to be found.

RM: Several banking markets offer a window into the future but most are still in the early stages of fintech adoption. Sweden is at the forefront but thus far local banks have been able to offset increasing competitive pressure by partnering with tech firms, slashing branch distribution, building out asset management units, and raising prices in low-return products. Korean households have quickly adopted many digital banking platforms over the last two years but successful incumbent banks are thriving by partnering in some form with these digital banks, cutting branches, and finding paths to improve their low products per customer stats. Fintech is growing rapidly in the UK as are private capital investors, largely to the detriment of local banks. Under the weight of these competitors, along with low rates, heavy regulation, and Brexit, UK banks are expected to earn a paltry 7% ROE in 20215.

Q: You mentioned before that banks often have low valuations – do current prices discount these risks?

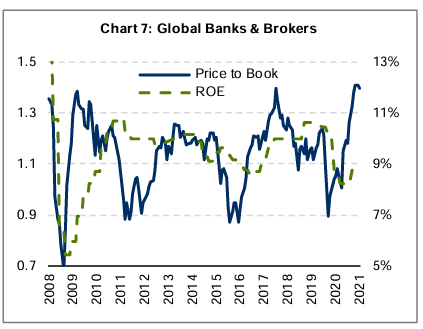

RM: Generally speaking, no. Current global bank valuations imply that ROEs will rise to pre-financial crisis levels when rates were much higher and regulation was lax (Chart 7). We think this outcome is unlikely and that bank stocks in general present unattractive risk/reward opportunities. This is particularly true given our view of the heightened risk for disruption going forward.

Q: Where are you finding value in global financials?

RM: We see significant opportunity in financials, specifically clustered in two areas: 1) property & casualty insurance and 2) exchanges. Our property & casualty insurance investments should benefit from the combination of the strongest competitive environment in decades, increased demand for risk-reduction products, considerable cost control, and any increase in economic activity. Our exchange holdings have sustainable competitive moats and are shifting their business mixes to proprietary high-margin products like data and clearing services. In both of these areas, we think that the snapshot of current valuation multiples does not capture the forward-looking opportunity.

So often in the environment of the twenty-four hour news cycle and societal short-termism, the true underlying issues driving headlines are missed or underappreciated. We hope this interview with Rich and Glenn serves as an additional resource to deepen your understanding of the opportunities and risks within the global banking industry. As always, please let us know if you have any feedback or would like to discuss these topics in greater detail.