I recently spent two weeks traveling in Japan, meeting with leaders across a range of industries, from banking to real estate to industrials to technology. Over the past several decades, our team has visited the country consistently, helping us find many “diamonds in the rough.” We have noted positive – albeit slow – developments across the corporate landscape, particularly over the past several years. Increasingly, I have heard investors speaking of enormous change underway in Japan, but my trip revealed a more nuanced story of continued incremental progress rather than radical change.

In short:

- Capital allocation – improving, but only gradually

- Pricing and profit margins – greater discipline than expected

- Free cash flow – an underappreciated problem

- China – increasing risks regarding competition and manufacturing footprints

- Consumers – the outlook is brightening

Context and Opportunity

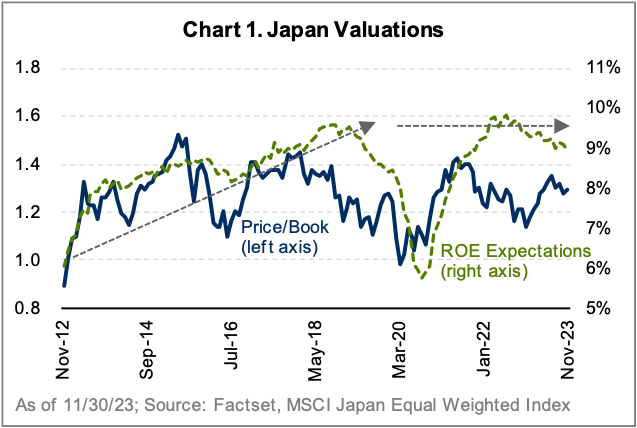

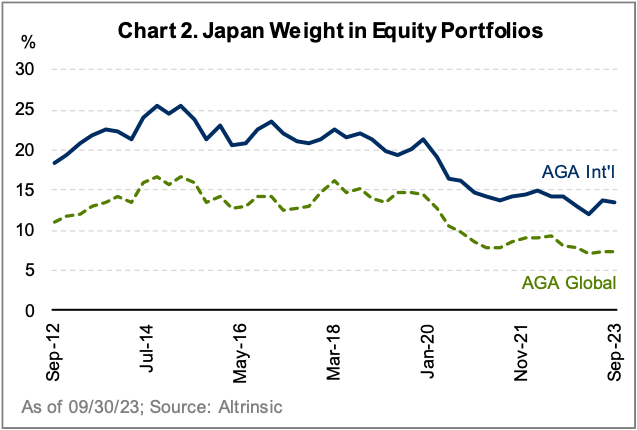

Since “Abenomics” began in 2012, corporate Japan has been on a path to improve return on equity, aided by significant monetary stimulus, a weak currency, increased investor activism, and corporate governance reforms. In the early years of Abenomics, Japan offered a compelling mix of improving financial productivity (return on equity) and low valuations (Chart 1). Given these dynamics, Altrinsic’s international and global portfolios were relatively heavily weighted in Japan from 2012 to 2019 (Chart 2). Over the last few years, however, our exposure has declined as value was realized and we found better opportunities elsewhere. Value still exists in Japan, but several stocks fit into one of three unattractive baskets:

1. Companies that significantly improved profitability and governance (and are valued accordingly)

2. Highly cyclical businesses with adequate quality but valuations that provide little margin of safety

3. Companies that are highly complex, volatile, and slower to improve corporate governance, resulting in cheap valuations (but for good reason)

Incremental Progress, Not Radical Change

Japan is fully re-opened, and we were excited to book nearly 40 meetings with contacts across industries. As always, stock selection is key, and context is important to consider when assessing the quality of information shared during each discussion – and the associated implications. With that said, several common themes emerged, shaping our perspectives about the investment opportunity set in Japan.

1. Capital allocation – improving, but only gradually

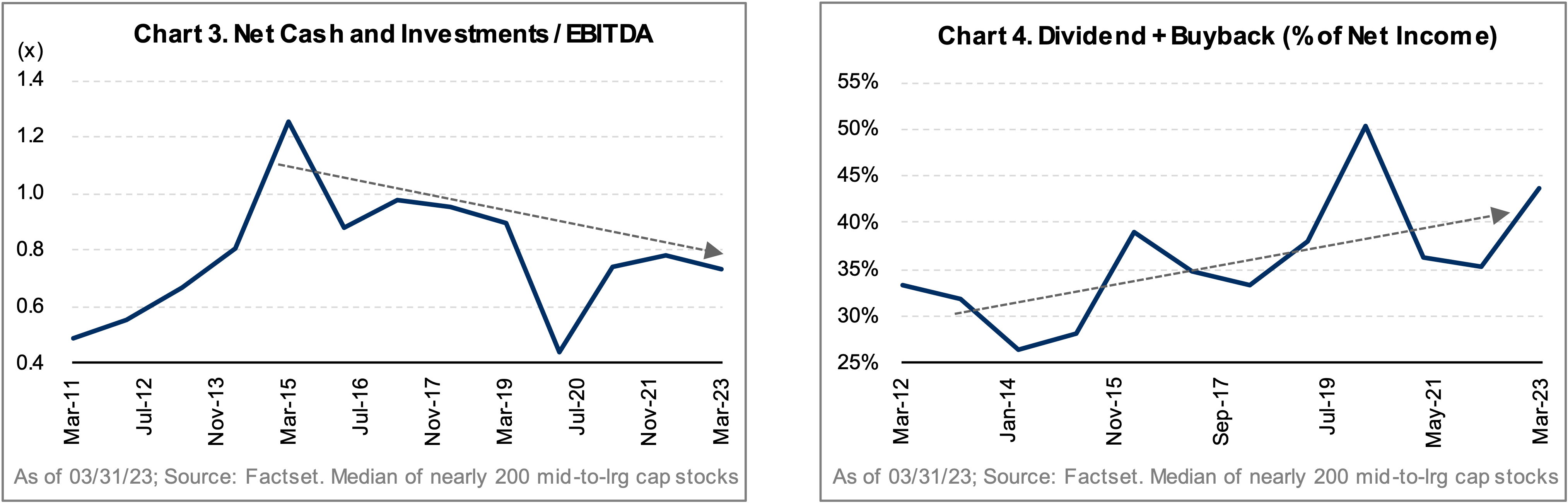

The average Japanese company operates with net cash on the balance sheet, which is very different from most global companies. For decades, Japanese businesses increased their cash holdings and maintained large equity investments in customers and suppliers. Over the last eight years, however, this has steadily declined (Chart 3), partly due to increased activism. Dividends and buybacks have been on an upward trend for years (Chart 4), and most company executives we met signaled a willingness to gradually improve these in the future. Simultaneously, we noted very little comfort in reducing cash or sharply improving cash returns to shareholders. Even companies at the forefront of corporate governance, like insurer Tokio Marine, said it would likely take close to a decade to eliminate its “strategic” shareholdings in its customers. Banks we met offered similar insights, saying that despite the improving Japanese economic environment, corporate credit demand remained modest at best.

Another related issue is complexity. Many Japanese corporations operate with high levels of diversification from both a product and location perspective, as they believe this reduces profit volatility. In theory, this makes sense, but in practice, a troubled segment hinders overall profits, and a lack of focus weakens scale and profit margins. Many international investors believe that corporations in Japan will rapidly simplify, but this was not echoed during most of my meetings. There are surely examples of change – Sony is planning to spin off its financial services division, and Mitsubishi Electric is spinning off its auto components business – but these are more the exceptions than the rule. Many larger financial institutions also remain highly complex, and thus, the opportunity linked to an improving interest rate backdrop is partially offset by significant lending risks abroad. From our many interactions, we believe that simplification in Japan will be very stock-specific rather than broad-based in the medium term.

2. Pricing and profit margins – greater discipline than expected

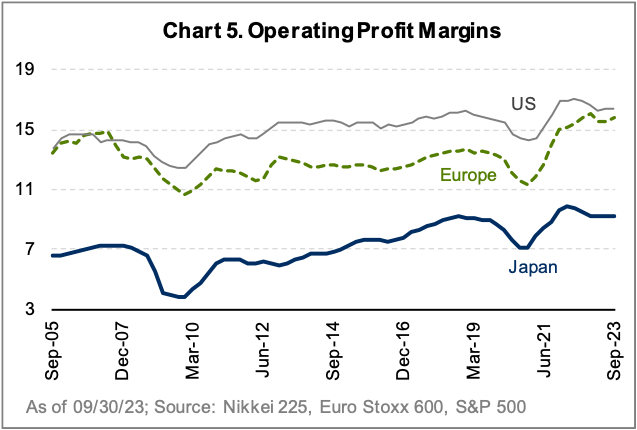

Corporate Japan operates with lower margins than its global peers (Chart 5). Many Japanese companies were slow to adjust to rising global inflation, which initially hampered profits, but on this trip, I consistently heard a much greater willingness to increase prices going forward. Despite a broad unwillingness to exit whole business lines, there is a greater emphasis on profitability per product, which is an important strategic shift. On the cost side, Japanese companies historically maintained more bloated cost structures due to a hesitancy to reduce staff count. Several senior leaders we met seemed willing to adjust costs, but plans were incremental, not transformative. Japan is on the right path, and the weak yen should help improve cost competitiveness for its exporters, but progress in many cases will be slow and steady.

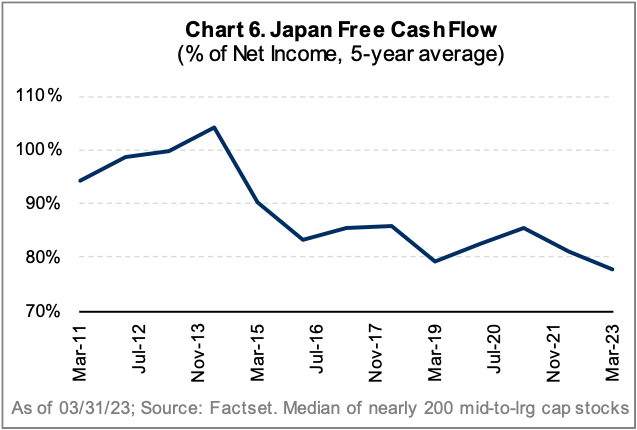

3. Free cash flow – an underappreciated problem

The topic of free cash flow garners little attention in Japan, a stark contrast to many other regions around the world. In most of my meetings over the last few years, Japanese management teams were quick to talk about return on equity and operating profits but expressed little to no focus on cash flow. Weak working capital management (higher inventories and longer accounts receivable terms) and high capital expenditures (at times not closely tied to adequate return objectives) contribute to the cash flow issues. Free cash flow as a percentage of net income at Japanese companies has steadily declined, now averaging less than 80% (Chart 6). While the average Japanese company trades at only 15x profits, it trades closer to 21x free cash flow. At Altrinsic, we consider investments as outright owners; thus, free cash flow is paramount. We continue to engage with Japanese management teams, encouraging a greater focus on free cash flow.

4. China – increasing risks regarding competition and manufacturing footprints

China remains an important trading partner for Japan despite sometimes contentious political relations. During several meetings, we heard concerns about two China-related risks, in particular, that have accelerated throughout 2023. First, many Japanese companies across sub-sectors, including factory automation, semiconductor equipment, and chemicals, are experiencing greater Chinese competition. These competitors are often pricing at a level that Japanese senior leaders see as loss-making or generating inadequate profitability. Reasons for this may involve a combination of slowing internal demand and rising political pressure to create more “home grown champions.” Japanese companies do not appear to be chasing Chinese competitors down the profit curve, but this presents risks to long-term profitability nonetheless.

The second growing risk relates to supply chains. In recent months, Japanese exporters have found that both Chinese politicians and Chinese customers are increasingly demanding that more products be produced locally. China’s own struggles with losing manufacturing to near-shoring and on-shoring could be driving this sentiment. Many of the Japanese management teams dealing with this issue shared that they see no other option but to move pieces of their supply chains into China in the coming years. This adjustment presents underappreciated risks to profitability and cash flows for some Japanese companies, but others in Japan (and internationally) may benefit if their supply chains are less China-dependent.

5. Consumers – the outlook is brightening

Consumer sentiment on the ground in Japan was less optimistic than I expected, driven by ongoing inflationary pressures, lagging wage increases, and yen sensitivity. This sentiment has likely contributed to the collapse of Prime Minister Kishida’s approval ratings to under 30%, one of the worst among major leaders in the developed world. Despite the mixed sentiment, the outlook is brighter than I anticipated. Long-term rates in Japan are shifting higher, but at current levels they are not a pressure point. Household leverage is manageable, and asset levels are quite high, leading to one of the highest household net worths relative to disposable income in the developed world.1

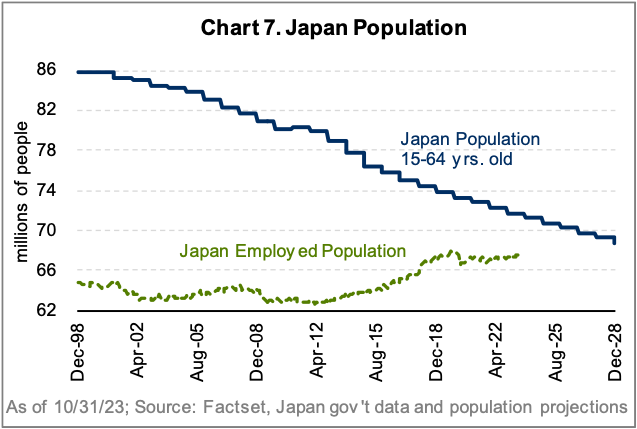

The labor market is also extremely tight, with an unemployment rate near 30-year lows (sub-3%).2 Employees hold more power as the pool of potential employees shrinks (due to age) while demand for employees continues to rise (Chart 7). I’ve been visiting Japan for many years, and even during other bouts of inflationary optimism (2015), most Japanese businesses were generally unwilling to increase employee wages. This time was notably different. Management teams consistently signaled a willingness to boost employee earnings, likely buoyed by growing corporate pricing discipline and a tighter labor market. If this is executed, it would be extremely helpful in Japan’s attempt to exit deflation.

Closing Thoughts

Japanese corporations stand to benefit from several tailwinds, including a highly stimulative monetary policy, increased investor activism, currency benefits, and a recent shift from deflation to inflation. In addition, the country’s equity market is experiencing renewed foreign investor interest after years of outflows from this group. Many companies in Japan have incrementally improved profitability and corporate governance, and we expect this to continue – but the path will not be simple, or rapid. Discerning whether Japanese companies are “cheap” or actually “undervalued” depends on deep and pragmatic analysis, along with significant management engagement. As the saying goes, “trust, but verify.”